This research rabbit hole is brought to you by: that time I saw a full cruet set in an antique store and became obsessively curious about them. And by: that time I then found a great deal on one because two of the bottles had been broken by a previous customer in the shop. And by: that still later time I found a full set of bottles in yet another antique shop for yet another great price!

Late in the 17th century, as dining rituals began to coalesce among European aristocrats (each region developing their own rules and standards, of course), the culinary use of oil and vinegar also began to grow in popularity. Along with common seasonings like salt and pepper, this brought about the development of a caddy to corral condiments that would need to be shared around the table. In upper class homes where footmen served the many courses, the caddy – called a cruet or caster set – sat on the sideboard and was carried around the table and offered to each person as needed. In middle-class homes, the caddy would have been placed directly on the table within reach of the diners.

By Victorian times, the cruet set had become a standard piece of tableware both in Europe and the United States. It’ll come as no surprise that the finest homes had sets with a frame made of ornate silver, and the glass bottles were of cut, colored, or etched glass. With the rise of silver-plating in the mid-1800’s, cruet sets became more affordable for middle class homes and also became popular wedding gifts of the era.

The frames held from three to eight bottles, but three and five slots were the most common configurations. Victorian sets included shakers for salt and pepper, and cruet (stopper) bottles for oil and vinegar. But what was in the fifth spot? This, oddly enough, became something of a mystery after cruet sets went out of general use.

Historians in the mid- to late 20th century had quite a time reaching a conclusion, but the general consensus based on primary sources (including period advertisements, catalog listings, and cookery books) seems to be that the fifth bottle (or third, in a three-piece set) held powdered mustard. In the days before refrigeration, which would have been required for pre-mixed cream mustards, each person at the table would use a portion of powdered mustard mixed with water or vinegar to create a custom meat seasoning.

Rather than being a shaker, this bottle often had a hinged lid with an opening into which a very small spoon could be set. Less common theories suggested white pepper, paprika, and cayenne pepper as possible inhabitants of the last bottle, but most evidence supports the use of powdered mustard.

Popular oils on the table would have been olive or sunflower, while vinegars may have been malt (common in Britain), white wine, infused/flavored, or balsamic.

Of course, times and tastes change, and as this happened the need for cruet frames and sets began to wane. By the 1920’s, prepared cream-style mustards such as Grey Poupon (introduced in 1866 and first imported into the U.S. in 1901) could be safely kept and set out on the table as needed in small pots. Oil and vinegar were also used at the table less frequently.

There was a brief phase where a three-slot frame included a toothpick holder in the third spot, but eventually frames were reduced to two slots for salt and pepper. Today, frames have largely been eliminated with the notable exception of salt-and-pepper caddies used in restaurants.

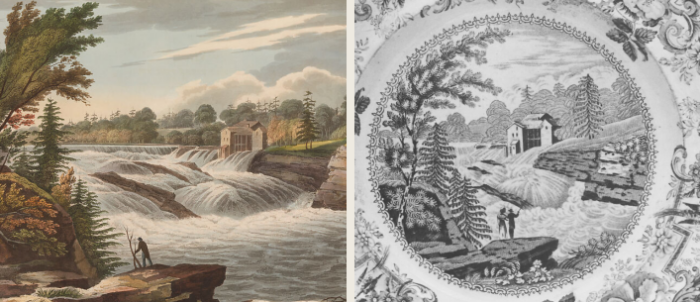

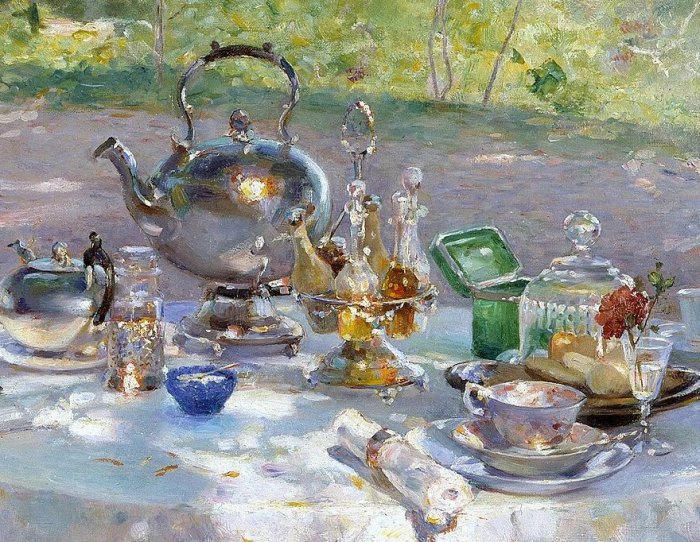

Side note: One of the things I love about researching stuff like this is that you can often discover something else you didn’t know about. In this case, I found a beautiful painting depicting the use of a cruet set! Below is just a small frame of detail – but, do look up “Breakfast Time” by Hanna Hirsch-Pauli (1864-1940). Since the piece was painted in 1887, I would consider it a primary source showing a period form and style of cruet frame. Be sure to click the link in the caption to see the full painting.

Finally, just to show you (as if you needed proof) that I am susceptible to being influenced by my own research rabbit holes, I give you my latest acquisition: a beautiful five-slot cruet frame with gorgeous cranberry glass bottles. I found it on Ebay “for a song,” as they say. It arrived badly tarnished, but cleaned up beautifully!

We haven’t been able to precisely date it, but cranberry glass reached its height of popularity in the mid- to late-1800s, which was also the height of the five-slot cruet caddy. And, the technology of electroplating silver to various base metals was beginning to eclipse previous plating technologies around that same time. Silverplated cruet sets reached a peak as popular wedding gifts in the 1880’s and 90’s. So I think it’s safe to say the set is from the second half of the 19th century, probably around 1890. That’s just a guess, of course, but it’s based on the convergence of several factors. What a beauty!